Promoting Romance Novels in American Public Libraries

For some time, romance novels have been regarded as a “scorned” genre.1 Due to the questionable status of romance fiction, many of the articles published in the professional literature are explanations of the romance genre for the uninitiated and defenses of the status and importance of the romance genre for readers.2 These types of articles have appeared with some regularity over the past twenty-five years. Books and articles on romance in public libraries have suggested strategies for promoting and publicizing the genre. However, little data have been published that indicate how common it is for public libraries to promote romance novels and the romance genre.

Romance novels are certainly a common feature of libraries’ collections. A 2006 survey of public libraries indicated that 99.7 percent of responding libraries developed their romance collections through purchase or donation or both.3 However, libraries do more than simply make books available. They also promote reading and encourage people to meet with others who enjoy reading. We wanted to find out if libraries were promoting the romance genre, and if they were, how they were going about that promotion.

The Literature on Romance Promotion

While most of the works published in the LIS literature have provided extensive explanations of the romance genre, its appeal, and its subgenres, a closer reading indicates that some librarians have been looking toward romance promotion as a necessary supplement to collection development.

Kristin Ramsdell’s Romance Fiction: A Guide to the Genre makes several suggestions for romance promotion.4 Her suggestions range from informal (introducing romance readers to each other) to formal (establishing a romance reader interest group at your library), including displays of romance and related works of nonfiction, keeping a romance review file for readers. She even recommends promoting romance in the local media, through means of book review columns in the newspaper or romance booktalks on local radio and TV shows.5

Ann Bouricius’ Romance Reader’s Advisory: The Librarian’s Guide to Love in the Stacks suggests passive reader’s advisory service such as making available bookmarks of romance authors and titles, posting lists of award-winning romance titles, and displaying romance novels prominently near the circulation desk.6 She also suggests more interactive ideas like sponsoring romance-reading programs, creating bulletin boards for romance-reading patrons to share ideas, and encouraging book discussion groups to read romance.7

Ramsdell and Bouricius both emphasize the importance of knowing the genre and its readers. They also emphasize the importance of making your library “romance reader friendly,” and developing an encouraging, positive attitude among staff toward romance fiction and romance readers.

Cathie Linz, Ann Bouricius, and Carole Byrnes offer suggestions for shelving and display of romance novels in order to increase their visibility within the library.8 They also cite examples of romance book clubs held in public libraries and providing resources such as romance trade magazines and Internet resources.9 John Charles and Cathie Linz mention several methods that can be used to promote romance, “. . . booklists or bibliographies, displays, programs, or even book discussion groups.”10

There is also evidence that some libraries have already been working to promote romance. The Romance Writers of America (RWA) conducted a 2007 contest called “Libraries Love Romance.”11 The contest had two categories, one for romance programming and events, and the other for romance collection and display. The multiple candidates for both of these awards suggest that at least some libraries have been actively promoting the romance genre in a variety of ways.

Research Questions

A survey of public libraries in the United States in 2006 asked about libraries’ collection development practices and attitudes relating to romance novels and the romance genre.12 Two questions on that survey form asked about book promotion and cultural programming related to romance novels.

The first question asked, “How does your library offer romance-related book promotion?” Respondents were given the following possibilities as choices:

- displays of romance novels;

- readers’ advisory (RA) assistance with romance novels;

- provides general RA tools (such as NoveList or Genreflecting);

- provides romance-specific RA tools (such as What Romance Do I Read Next? or Happily Ever After: A Guide to the Romance Genre);

- provides romance-specific magazines, e-zines, or journals (such as Romantic Times Magazine); or

- other.

The second question asked, “Does your library offer romance-related cultural programming?” Respondents were given the choices of:

- romance-oriented book discussion groups;

- romance author visits or book signings; or

- other.

Results

Surveys were sent to 1,020 directors of public libraries identified in American Library Directory using a purposive sampling technique in which we randomly selected libraries from each state. By December 2006, 396 usable surveys were received for an effective return rate of 39 percent.

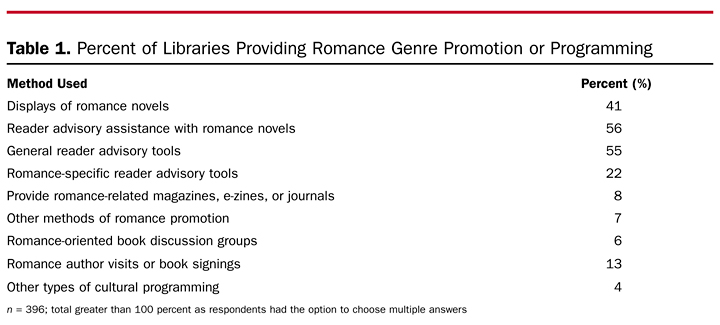

As table 1 shows, RA services are the most commonly offered method of romance genre promotion, and general RA tools are available at over half of all responding libraries. Slightly fewer libraries use romance novel displays, though this was still a popular method of promotion. Romance-specific RA tools and magazines were less commonly provided. Some of the respondents who used “other” methods of promotion described the methods they used. These included separate shelving for romance titles, romance-specific spine labels, bibliographies and booklists, promoting romance in the library newsletter, and a Popular Authors Club promotion.

Of the programming options we provided, romance author visits and book signings were provided by over 10 percent of the responding libraries. Romance-oriented book discussion groups were only provided by 6 percent of libraries. Some of the “other” means of romance-related programming were a special Valentine’s Day romance book sale held by the Friends of the Library, romance booktalk presentations to local associations such as Rotary Club, and one library said they had a chapter of Romance Writers of America meet at their library. Only 3 percent of libraries (12) indicated offering more than one type of romance-related programming.

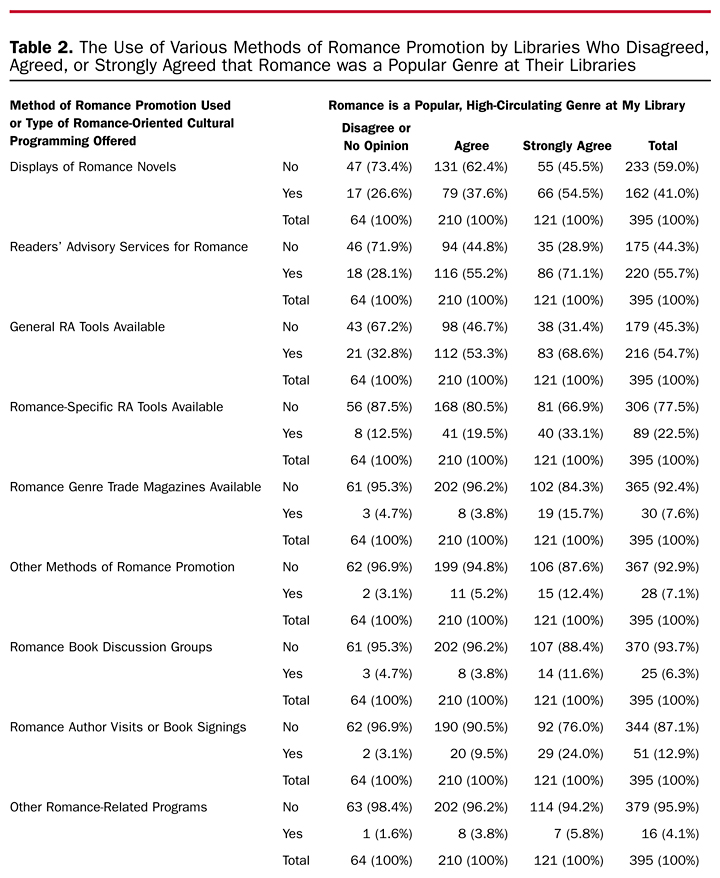

When asked whether romance was a high-circulating, popular genre at their libraries, 53 percent (210) “agreed” and 31 percent (121) “strongly agreed.” Ten percent (41) had no opinion, while 6 percent (23) of respondents “disagreed” or “strongly disagreed.” There was one missing response. The “no opinion,” “disagree,” and “strongly disagree” responses were collapsed into one category, leaving three categories for analysis: “strongly agree,” “agree,” and “no opinion or disagree.” Results in table 2 indicate that as perception of romance popularity increases, so does the percentage of libraries using various methods of romance promotion. For instance, romance novel displays were used at 27 percent of libraries where romance was not perceived to be popular. That figure increases to 38 percent of libraries agreeing that romance is popular at their library, and increases again to 55 percent for libraries that strongly agree. This relationship of increased use of promotion methods with increased perception of romance popularity holds for all methods of romance promotion suggested.

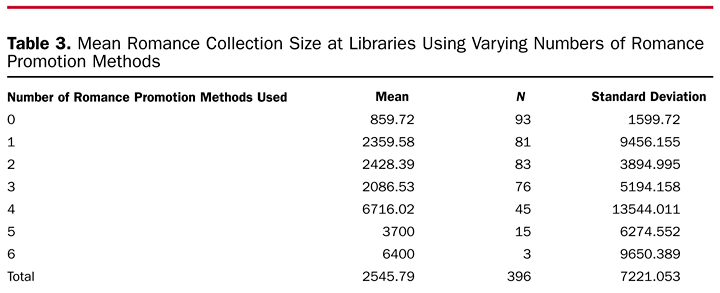

Looking at romance promotion and programming based on mean collection size provides another way to look at the relationship between library commitment to the romance genre and their promotion of that genre. As indicated in table 3, 77 percent (303) of responding libraries offered at least one type of romance promotion. Many offered multiple forms of romance promotion: 56 percent (222) offered at least two forms of promotion, 35 percent (139) offered at least three, and 16 percent (63) offered at least four types of romance promotion.

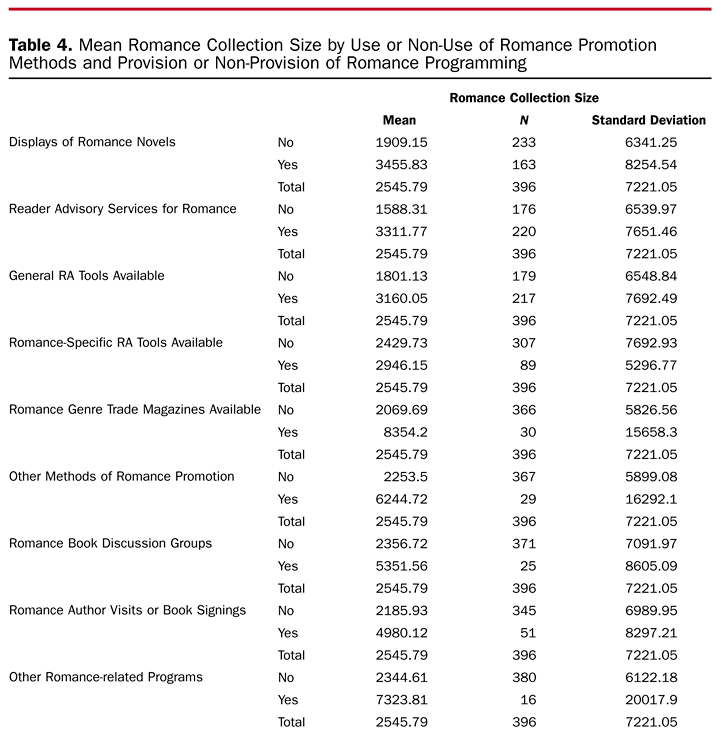

Table 4 provides mean collection size of libraries using multiple methods of romance promotion. Those libraries that use no promotion methods have smaller mean collections than libraries that use one or more methods. Libraries using four promotion methods have the largest collections of all. Those libraries that invest more of their collection funds into romance novels seem also to use more strategies to get those novels into the hands of readers.

Total romance collection sizes reported by our respondents varied from 0 to 75,000. This wide variance in collection size made for large standard deviations in table 4. In general, however, libraries that used fewer methods of romance promotion also had less variability in romance collection size.

Looking at both scenarios, romance collection size and perceptions of popularity, methods of publicizing the romance genre appear to be more widely used in libraries where the romance genre is more firmly entrenched. The fact that romance promotion increases with increased perception of the popularity of the romance genre does not necessarily imply that one factor causes the other. It is difficult to say whether the librarians answering this survey saw multiple methods of promotion being used, and from that evidence, decided romance was popular; or whether they knew romance was popular, so developed multiple methods of promoting the genre to take advantage of that popularity.

Being Seen Promoting Romance

Part of the challenge of promoting romance is being seen promoting it. It’s not enough to provide romance RA and expect readers to use that service. As Ramsdell and Bouricius note in their books, readers may not feel comfortable seeking assistance in finding good romances unless they see that romance RA is as commonplace a library activity as mystery or science fiction RA.

Libraries can provide this atmosphere by developing romance book displays, making romance RA tools visible in their collections, and providing information on their websites about romance. Ramsdell suggests making contacts with romance readers and with bookstores, becoming a visibly “romance-friendly” librarian in the community.13

Providing the Tools for Romance-Specific RA and Collection Development

Most general RA tools contain information about romance among their offerings. Genreflecting, NoveList, and What Do I Read Next? all include romance-oriented content. However, romancespecific RA tools might also aid libraries in being seen to promote romance within their libraries. Some of the more common romance-specific RA tools include Ramsdell’s Romance Fiction: A Guide to the Genre or Ann Bouricius’ Romance Reader’s Advisory: The Librarian’s Guide to Love in the Stacks. Using and displaying these sources helps readers to know that romance reading is considered as worthy as any other kind of reading.

Book Displays

Kristin Ramsdell’s romance review columns for Library Journal list romances that follow a particular theme or plotline. It would be easy for a library to create small displays using these suggestions and local wisdom. Because these lists are available at the Library Journal website, a library could easily link to these reviews on their own webpage. Many libraries also make reviews available in their online catalogs via Syndetic Solutions, Inc. or LibraryThing for Libraries.

Ramsdell suggested displays of romance novels alone and with other related materials (e.g., travel guides for location-specific romances), provision of bookmarks and flyers, and cross-referenced files featuring reader reviews of romance novels. In another form of book display to reach an audience outside the library, she suggests writing romance review columns for the local newspaper, review shows on theradio or television, and booktalks or author panels at local libraries.14 Additionally, RWA makes promotional posters available for bookstores and libraries to download and use through their website at www.rwanational.org/cs/booksellers_and_librarians/rwa_poster_gallery.

Virtual Romance Promotion

Libraries can promote the romance genre virtually, too! Many libraries publish read-alike lists for their patrons. When these lists are used in bookmark form, there isn’t much space to waste. Posted on the Web, however, these lists can include annotations and personal reflections. The St. Louis Public Library website features romance novels recommended by staff members, including annotations, at www.slpl.org/slpl/gateways/article240094736.asp. Lists can also be individual to the library. For instance, the Northbrook (Ill.) Public Library provides an annotated list of romance novels by Illinois authors at www.northbrook.info/lib_illinois_romance.php.

Many public libraries’ webpages link to RA databases like NoveList or What Do I Read Next?, where Web patrons can seek additional reading recommendations. Those libraries that do make RA databases available online can create links to these databases on their pages for each genre, including romance. Those libraries that cannot make these databases available can still provide content for romance readers. The Internet Public Library has a list of romance resources on the Web, with annotated links to sites such as All About Romance, The Romance Reader, and the Romance Novel Database. Many libraries,

including the Toronto Public Library, include these sites on their romance and fiction pages, to expand the information they are able to provide.

Romance-Oriented Programming

Ramsdell also suggests recruiting readers to develop “romance readers interest groups” to aid in collection development.15 These groups might act as advocates for the genre, and help produce RA materials to assist other romance readers.

Public libraries can and do provide romance book groups. In a discussion of the literature about book group formation, Joan Bessman Taylor found several instances in which romance and other genre works were not considered appropriate for discussion groups.16 She cites Seattle Public Library’s online guide, which indicates that various genres including romance “leave little to discuss” because they are too plot-driven.17 Even so, Taylor indicates that some of the groups she studied did discuss genre fiction successfully.

While romance novels may not be appropriate for discussion of the book’s content, there are opportunities to discuss romance novels with regard to the larger societal context or with regard to other romance novels or life experiences. Christine Jarvis used romance novels with women in an adult education program to evaluate larger societal issues like the “romance discourse” in daily life and power relationships.18 The romance novel may not create its own world in the same way that a standard novel has to, because romance novels reflect the world around them.

Book signings and author visits are strategies for bringing romance authors to the readers themselves, either in person at the library or virtually. Many romance authors are also librarians or former librarians, and may be amenable to being asked to do book signings or author discussions at the library. The RWA webpage (www.rwanational.org) suggests several strategies to bring romance authors to library patrons, including blogging, podcasts, and workshops. Libraries with small programming budgets may want to team up with other area libraries to ask an author to do a short regional tour. Multiple libraries might team up to sponsor a webcast romance author panel discussion. Romance is among the most accessible genres, and promoting romance may help readers see themselves as writers or more appreciative readers.

Programming for Teens

Given that 64 percent of libraries indicated that they collected teen romance, we would be remiss if we failed to mention the possibilities for romance-related programs with teens. The 2008 release of the movie Twilight, following its 2005 publication by author Stephenie Meyer, allowed young adult librarians to cross-promote the book with the movie, and also to promote other teen romance and paranormal books. From creating read-alike lists of teen romances to video-recording teens doing booktalks about Twilight to sponsoring Twilight-themed events where teens dress us as their favorite characters, young adult librarians

have been using their programming and RA skills to keep young adults reading.

Conclusion

Survey results indicate that the romance genre is being promoted to encourage people to read romance fiction. Half of all responding libraries provided RA service for romance, and four out of every ten created romance displays. Many libraries realize that romance fiction can be used to draw people in and encourage readers to discover new authors through RA services catering to romance readers. Romance-oriented programming is less common, with only one-tenth of responding libraries holding author visits or book signings, and one-twentieth holding romance-related book groups.

Beyond being recognized as places for people to obtain books, many libraries aim to be public spheres where people come together to exchange ideas and share information. Romance readers can interact with each other through book groups and with authors through programs. New romance readers can be recruited through these programs, and myths about the romance genre can be put to rest when romance readers interact with non-romance readers.

Promotion and programming for the romance genre can be used to retain current romance readers at the library; it may also be useful for drawing new faces to the library—those who had not thought the library was particularly welcoming to romance readers. Potential controversy over a library’s promotion of romance fiction can even be construed as a positive opportunity to share the multiple benefits of reading. Reading is done for many different purposes and at many different levels. Libraries support those purposes without dictating what should or should not be read.

Editor’s note: The authors would like to thank the Romance Writers of America for providing funding for this project through their Research Grant Program.

References and Notes

- Lydia Cushman Schurman and Deidre Johnson, eds., Scorned Literature: Essays on the History and Criticism of Popular Mass-Produced Fiction in America (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Pr., 2002).

- For examples of this type of literature, see Mary K. Chelton, “Unrestricted Body Parts and Predictable Bliss: The Audience Appeal of Formula Romances,” Library Journal 116, no. 12 (July 1991): 44–49; Jayne Ann Krentz, “All the Right Reasons: Romance Fiction in the Public Library,” Public Libraries 36, no. 3 (May/June 1997): 162–66; Johanna Tunon, “A Fine

Romance: How to Select Romance Novels for Your Collection,” Wilson Library Bulletin 69, no. 9 (May 1995): 31–34. - Denice Adkins et al., “Romance Novels in American Public Libraries: A Study of Collection Development Practices,” Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 32, no. 2 (2008): 59–67.

- Kristin Ramsdell, Romance Fiction: A Guide to the Genre (Englewood, Colo.: Libraries Unlimited, 1999).

- Ibid., 25–27.

- Ann Bouricius, Romance Reader’s Advisory: The Librarian’s Guide to Love in the Stacks (Chicago:ALA, 2000), 49–50.

- Ibid., 50–51.

- Cathie Linz, Ann Bouricius, and Carole Byrnes, “Exploring the World of Romance Novels,” Public Libraries 34, no. 3 (May/June 1995): 144–51.

- Ibid., 151.

- John Charles and Cathie Linz, “Romancing Your Readers: How Public Libraries Can Become More Romance-Reader Friendly,” Public Libraries 44, no. 1 (January/February 2005): 44.

- Romance Writers of America, Libraries Love Romance Contest, 2007, www.rwanational.org/cs/libraries_love_romance_contest (accessed Dec. 22, 2009).

- Adkins et al., “Romance Novels in American Public Libraries.”

- Ramsdell, Romance Fiction, 24.

- Ibid., 28.

- Ibid., 25.

- Joan Bessman Taylor, “Good for What? Non-Appeal, Discussability, and Book Groups (Part1),” Reference & User Services Quarterly 46, no. 4 (Summer 2007): 33–36.

- Ibid., 35.

- Christine Jarvis, “Love Changes Everything: The Transformative Power of Popular Romantic Fiction,” Studies in the Education of Adults 31, no. 2 (October 1999): 109–23.

Tags: romance, romance novels, romance readers and the public library